Love Doesn’t Wait On Understanding

Love doesn’t have to understand its object fully.

Indeed, it never can.

As for love, so for empathy and compassion.

A human being, and all of her experiences, can never be fully understood.

No one even fully understands himself – let alone anyone else.

Parents do not fully understand their children – but they love them nonetheless – even unconditionally.

We make a huge mistake when we demand that others must understand us – and on our own terms – before we accept their compassion or allow ourselves to have compassion for them.

This demand to be understood as different seems to be an increasingly accepted cultural norm that is making it harder for us to love each other and even to remember that we are all fundamentally the same.

In recent years, acts of hate, fear, and abuse have been committed against thousands of individuals – as they always have been. Those individuals, being individuals, belong to various identifiable segments of the population or – as they always have had.

Some are women; some are black; some are Asian, and so on.

It is always a good thing when one human being comes better to understand the experiences – and especially the plight, the challenges, and burdens – of another.

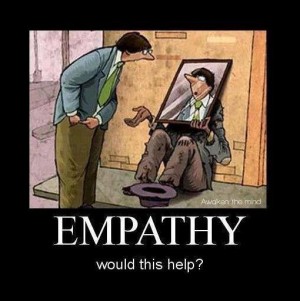

Yet, if we can’t fully understand ourselves, our own motivations, and our own responses to things –– how can we possibly understand or, more to the point, experience, the world as it is experienced by another?

We are finite beings in a world of infinite complexity, infinite uncertainty, and experiences that cannot be precisely communicated.

Accordingly, we can go as far in understanding our fellow man or woman as our shared experience, humanity and palette of emotions, felt by all of us for broadly the same reasons, allows. In other words, our empathy goes as far as is enabled by what we share in common.

Even a university professor who has studied for a whole lifetime one nation, one ethnicity, one gender, or any single group of people, would not completely understand them. Indeed, if he spent his whole life studying just a single person, he’d still not know what it felt like to live as her, or why she felt whatever she felt and when.

Obviously, though, the impossibility of such knowledge doesn’t stop one person having compassion for another; it doesn’t stop one person doing the right thing; it doesn’t stop one person calling out abuse when he sees it.

One might say the lack of such knowledge doesn’t stop us from knowing enough to do all of those things.

But today, more than ever in living memory, the first thing we are increasingly caused to focus on when an act of harm is committed is the group(s) to which the victim belongs. Thus, we are told, sometimes explicitly but more often implicitly, that the morality of our response, the rightness of our response, and the compassion in our response, depend on understanding that group – or something about all the people in it, especially if we are not members of it.

Such an understanding may well be required as the basis of effective changes of policy and so on – but it neither love nor empathy can be held hostage to it.

At a time where group identities have been elevated to the unquestioned starting points of so many of the moral and political discussions that reflect and shape our culture, it is worth reminding ourselves that the most humane response to any act of harm against a fellow human being is not, and should not be, mediated by his color, her gender, their disadvantages or our advantages. On the contrary, a response of pure compassion, humanity and empathy is one necessarily born of a shared identity as “human being” – so no other identity can possibly matter as much as that one. And nor should it be made to.

Commonality Favors Compassion

Have Americans started to shed more light on, and pay more attention to, acts of harm that reflect, and are used to reinforce, division and difference? To some of us, it feels that way.

All acts of abuse are unacceptable and creating a society that acknowledges that and acts accordingly depends on remembering (and perhaps even stating) as much whenever those with cultural influence try to insist that everyone’s response to any such act should be determined by, or give primacy to, some particular characteristic of the victim or, for that matter, the perpetrator.

Compassion doesn’t need color or race or gender.

Empathy doesn’t care about those things either. Of course, it will hear clearly the importance of such characteristics to the person to whom it is listening – but it will not make that listening dependent on them or use them to prejudge what it will hear.

What a person or a society focuses on is what it gets more of.

It is important, therefore, not to let our cultural and moral pendulum swing too far in the direction of attending to the identities that divide us.

It’s the identity that unites that matters the most.

Focusing on differences between people makes empathy harder – not easier. That is psychology 101. We’ve tested it to death and we all know it from our own experience.

Focusing on differences between people makes empathy harder – not easier. That is psychology 101. We’ve tested it to death and we all know it from our own experience.

Accordingly, let us take care to nurture those most fundamental and beautiful aspects of human nature that don’t change when they cross boundaries of identity. The purpose will be to counterbalance the prevailing trend in the Anglophone world, which reduces their power and scope, of paying so much attention to the things that make us different at the very moments when human suffering demands a response that is rooted in the one thing that makes us all the same – our shared humanity.

Understanding “the other” is important; but understanding is always incomplete, and its benefits take hold over time as it informs personal actions and public policies.

Loving “the other” is necessary; love can be experienced completely, and its benefits are immediate: they do not depend on, nor should they wait for, an understanding that can never be fully achieved.

Indeed, Love is most fully expressed upon the realization that, while we all live very different lives, ultimately there is no “other” at all.