One of my recent articles, “The Mistake You Make in Every Political Argument” (Mistake) made the claim that most political arguments that seem to depend on a disagreement over moral values actually hinge on a disagreement about empirical facts.

Mistake was shared by thousands of people of all political persuasions because they saw power in its diagnosis of, and prescription for, our incessant talking past each other when it comes to politics.

That article was always intended to be the first of two. This is the second, and it answers the core question left unanswered by Mistake. If you’ve not read Mistake, please do so before reading on from here!

That question left unanswered was, “If our political positions are based on the facts that we choose, then how do we choose those facts?”

This article will answer that question, and in so doing, also deal with an instinctive objection to the case in Mistake, loosely put, is “… but surely, people do have different morals, and that causes political disagreement too”.

In fact, both claims are true. Most political arguments hinge on factual disagreements AND people’s different morals cause them to have different political views.

But they depend on each other in a counter-intuitive way: our morals determine our political views mostly by determining subconsciously which facts we choose.

Mistake explained that we choose our own facts, and that the key to resolving a political argument (and many other arguments with moral content) is to discover how your opponent’s facts differ from yours.

But it didn’t explain you why your opponent chooses his facts while your choose yours.

That’s what this article will do. When you understand that why, you will also know the how of changing someone’s facts. In other words, I’m going to give you a specialized tool for hacking the process of political judgment formation.

Here’s the tool in one sentence:

In domains with moral consequences, such as politics, people believe the facts that, if acted upon, yield outcomes that are consistent with their moral intuitions.

These moral intuitions cover a wide range, and can be experienced as anxiety, disgust, revulsion, anger, shock, guilt, fear, delight, elation or being moved to tears, for example. They can be as powerful as any other direct perception, but cannot always be articulated unambiguously or objectively in a way every other person would get.

The moral intuitions of different people may be differently sensitive to different aspects of human experience. Some react more strongly to harm; some to injustice; some to oppression; some to disloyalty etc. as brilliantly described by Jonathan Haidt in his important book, “The Righteous Mind”.

As Haidt discusses at length, brain scans prove that our moral intuitive reactions to an occurrence or proposition do not come after we consciously determine whether it is good or bad. Rather, they precede it. In other words, moral intuitions are pre-conscious. Like other internal experiences, such as hunger or terror, they are there before conscious thought – and so affect that thought. And, as confirmed by extensive experiments across cultures, people can experience moral shock or disgust at an action or idea – even insisting it is wrong – even when they cannot subsequently provide any reason, based on their consciously held moral values, for their view.

A Moral Scientific Method?

I wrote “moral intuitions”. They might also be called moral instincts. But they are decidedly not the same thing as a “moral system” or consciously held “moral axioms”, “moral premises” or “moral values”. In fact, moral intuitions relate to a moral system or axioms as physical observations relate to physical theories.

If your values are your “moral theory”, then your intuitions are your “moral data”.

In the physical sciences, physical theories (principles) are modified to fit data (physical observations) – and not the other way around, because the data don’t care about theory.

In the physical sciences, physical theories (principles) are modified to fit data (physical observations) – and not the other way around, because the data don’t care about theory.

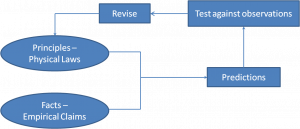

When a scientist examines an issue, he predicts an outcome by applying general physical principles (laws of nature) to relevant facts. If the physical world acts contrary to his prediction, as revealed to him by observation (physical data), then he knows there is something wrong. If he is sure of his initial facts, then the wrongness of his prediction causes him to revise his physical premises. (Fig. 1)

When a scientist examines an issue, he predicts an outcome by applying general physical principles (laws of nature) to relevant facts. If the physical world acts contrary to his prediction, as revealed to him by observation (physical data), then he knows there is something wrong. If he is sure of his initial facts, then the wrongness of his prediction causes him to revise his physical premises. (Fig. 1)

Figure 1. In science, the results of actions are tested against observations and theories are changed if the predictions are factually wrong.

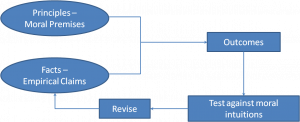

Analogously, in politics and other moral domains, a person predicts a morally favorable outcome by applying his general moral principles (values) to relevant facts. If the outcome is contrary to his prediction, as revealed to him by moral intuition (moral data), then he knows there is something wrong.[1]

Figure 2. In politics, the results of actions are tested against moral intuitions and empirical beliefs changed if the outcomes feel morally wrong.

But there is a critical difference between the physical and moral realms. Whereas in physical science, physical premises are revised in response to contradicting physical observations, in moral or political science, it is not just the moral premises that get revised in respond to contradicting moral intuitions, but more often and more importantly, the facts in which we believe. (Fig. 2)

That sounds counter-intuitive when written in the abstract, but you already know it instinctively.

How so? Because in nearly every case, when you are engaged in a moral or political argument, which Mistake demonstrated, invariably hinges on different beliefs about things in the world rather than moral premises, almost every move you make involves pointing out facts to your opponent.

To start with, of course, you have to point out the facts on which your position rests because you can’t make your argument without laying them out. But beyond that, when you find your opponent disagrees with you, you almost always present more facts that reinforce the relevance of the moral premise that you are bringing to bear on the question. Why? Because facts determine what moral values govern the issue or, in cases where multiple moral values clearly bear on the issue but pull in different directions, which values takes priority.

How do you choose, and what makes you instinctively share, the facts that you use in an argument?

You use facts to which you have a strong moral intuitive response. That response “tells” you that those facts are relevant to the issue because they determine which of your moral values to apply to justify your position on the issue. You unconsciously assume that sharing those facts will induce the same moral intuitions in the person you’re arguing with.

In other words, you’re instinctively marshalling facts in an attempt to induce in your opponent the moral intuitions that brought you to the position that you are arguing for.

The fundamental psychological reality that you’re exploiting when you do this is that of cognitive dissonance – and our need to eliminate it.

You’re trading facts (E.g. “Of course a fetus is human! What else could it be?”, “Four cells isn’t a human being.” “Guns don’t kill people. People do.” “Countries with fewer guns have fewer homicides.”… you get the idea… ) to generate in your opponent an uncomfortable moral intuitive inconsistency, and therefore a cognitive dissonance, with her own position.

The need to eliminate cognitive dissonance is the emotional mechanism by which our views are made increasingly consistent with each other and with our experiences in the world. In other words, it is the evolved mechanism by which we make our beliefs more true, which favors survival.

Hume’s Guillotine Is Broken – and It’s Upside Down

David Hume, the Scottish philosopher noted that moral values (“what is right”) cannot be derived from empirical facts (“what is so”). This insight is called “Hume’s Guillotine”.

Nevertheless, our moral intuitive systems do just that all the time – because neurologically, we are “wired” for our pre-conscious moral intuitive responses to turn our experiences of “what is so” into beliefs about “what is right”.

Therefore these intuitive moral reactions are how, in practice, we derive an “ought” from an “is” without being able to do so logically. They are the wrench that our brain puts in Hume’s guillotine.

Sometimes, a moral instinct can be consciously justified after it is experienced, by a consciously held, internally consistent, clearly articulated moral system. But often, it is not. Moreover, like scientists who ignore physical data that don’t fit their pet theory, people can ignore or suppress a moral instinct because it is at odds with a consciously held ideology, out of a sincere belief in that ideology or even an ego investment in it.

But whether we ignore them or not; and whether they fit our ideology, moral intuitions are the data that we use to test, and hopefully correct, our moral understanding of the world, just as scientists use physical data to test, and hopefully correct, their physical understanding of the world.

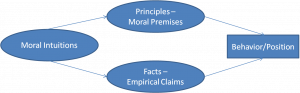

They don’t just inform our policy positions by determining our moral values directly: more importantly, these moral data tell us which part of our value system applies to certain things by causing us to believe certain facts about them, and to categorize or define them in one way or another. That is how primarily our moral intuitions cause us to judge right from wrong – especially when it comes to complex political issues.

And the more complex the issue, the more room there is for disagreement about which empirical facts are true, reliable and relevant.

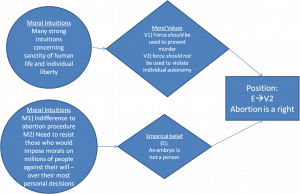

Figure 3. Moral intuitions affect our moral and political positions by determining both our moral premises and our empirical beliefs about the physical world. Our political disagreements are often driven by differences in empirical beliefs (a fetus is a person – very contentious) than moral premises (murder is wrong – not contentious), which tend to vary much less among people in a shared culture.

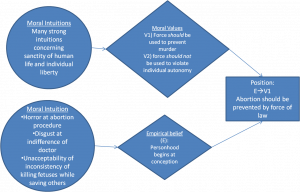

In Mistake, I considered the issue of abortion as an example. So let’s apply Fig. 3 to that issue for

Laurie (who is pro-life) and for Charlie (who is pro-choice).

Laurie

Charlie

Both Laurie and Charlie have many moral intuitions that cause them both to believe that murder is wrong and that the state has a duty to protect liberty.

But they have different moral intuitive reactions to the idea of abortion.

Laurie’s moral intuitions against abortion means that her belief about what abortion, and therefore what a fetus, is must make V2 (force should not be used to violate individual liberty) inapplicable and V1 (force should be used to prevent murder) applicable.

Charlie’s moral intuitions in accepting abortion means that his belief about what abortion, and therefore what a fetus, is must make V1 inapplicable and V2 applicable.

For each of them, it is their empirical belief that determines which of the values (V1, V2) is operative, and so is responsible for the disagreement between Laurie and Charlie’s positions on the abortion issue.

And it has to be that way, because there is no intuition about abortion that would cause either Charlie or Laurie to start accepting murder or violations of individual autonomy.

No. In neither case is either of these moral values at issue. Rather, it is the applicability of these values to the issue of abortion that, governed by the opponents’ empirical beliefs, which separates them.

Not only, then, do we derive an “ought” from an “is” via our moral intuitions: we derive an “is” from an “ought”. Hume’s guillotine isn’t just broken: it’s broken and upside down!

- Obviously, objective reality itself affects all our beliefs and predictions about the world, including our moral ones, but I’m taking that as given, since objective reality in the most fundamental sense (e.g. the laws of nature; what exists) does not vary among people. ↑